“I have worried about the (Korean) Peninsula being a place that could just explode almost more rapidly and more dangerously than anywhere else in the world,” said the recently retired top U.S. military leader. In a recent interview with RJIF, Admiral Michael Mullen, former Chairman of Joint Chiefs of Staff of the United States, emphasized the responsibility of China by saying, “I think China has to work as hard or harder than anybody else to create pressure on (North Korean leader) Kim Jong-un to back away from both the development of this (nuclear weapons) and, certainly, the potential use of nuclear weapons.”The admiral also pointed out that China’s long-term strategy is the second major challenge for the Japan-U.S. alliance. Regarding the tension in the South China Sea he mentioned, “I was pleased with the most recent freedom of navigation operation (FONOP) on the part of the United States, and we need to continue that.”

He emphasized the significance of Japan-U.S. Military Statesmen Forum (MSF) in dealing with these challenges. He said, “It allows us to tap the wisdom of very senior people, who have led in very difficult times, and to help the younger, the newer, generation of leaders evolve.” Toward the upcoming third meeting of MSF in July Admiral Mullen expressed his expectation to discuss the issue of civilian/military relationship among other topics, noting “The whole issue of the relationship between civilian leadership and military leadership, which is a much more complex area than I realized when I was living that life, is another one that I think there is a great value in.”

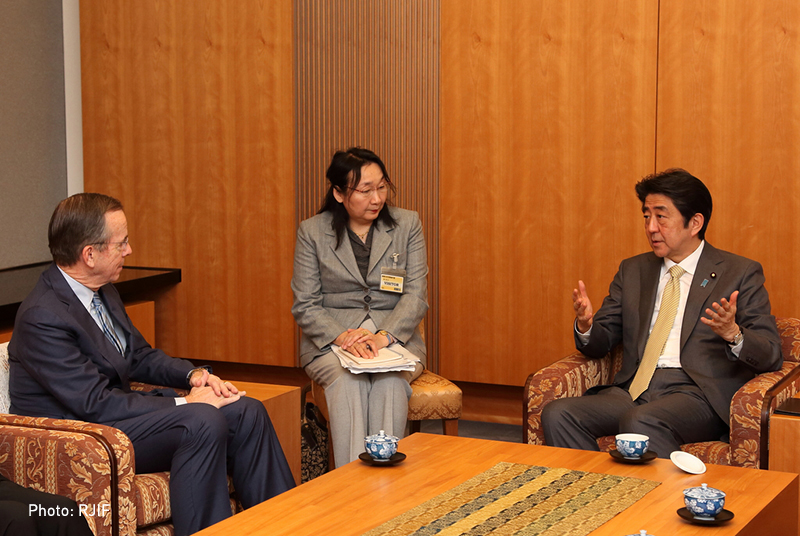

Admiral Mullen, one of the regular members of MSF, visited Japan from January 5-8 at the invitation of Dr. Yoichi Funabashi, Chairman of the RJIF. While in Tokyo, he met with the top leadership of the Japanese government, including Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and other major cabinet ministers. He gave this interview to Mr. Yoichi Kato, Senior Research Fellow of the RJIF prior to his return to the United States.

The following are the excerpts of his interview.

Q: During your visit to Japan in January you met Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, Chief Cabinet Secretary Yoshihide Suga, Foreign Minister Fumio Kishida and Defense Minister Gen Nakatani among others. What was your major takeaway?

A: I guess my biggest takeaway is how strongly they feel about the importance of the relationship between the United States and Japan, and how committed they are to it. And I tried to reassure them, as best I could, how important it was, from the U.S. perspective as well.

I am incredibly impressed by what I see, in terms of the current leadership, the issues that are being addressed, whether it’s the economy or the recent very powerful and important decision on the resolution of the “comfort women” issue between Japan and South Korea. I give President Park Geun-hye (of the Republic of Korea) and Prime Minister Abe a lot of credit.

I think that also opens up lots of doors in terms of meeting challenges here, from a trilateral standpoint: the United States, ROK and Japan. And certainly there are challenges. And, while the alliance is very strong and the relations are very strong, it needs to be strong now to meet the challenges. The day before I got here was the nuclear test in North Korea.

It’s a reminder of how serious issues on the Peninsula are, the challenges in the South China Sea, which continue to grow and the relationship with China. And then, for me, in particular, the importance of interacting with my former counterparts (Chiefs of Staff, Joint Staff of Japan), Admiral Takashi Saito and General Ryoichi Oriki, in terms of continuing to address and support those currently serving in the military and discussing and addressing those issues inside the RJIF within the Military Statesmen Forum.

Q: Looking at the recent developments in this region, including the North Korean nuclear test and what’s happening in the South China Sea, it seems that the regional strategic landscape could be described as being deteriorating.

A: I’m not sure I’d use the word “deteriorating,” as much as, obviously, it continues to change. And I think the biggest challenge that we have, the biggest longterm challenge we have here is how we all work together to figure out where China’s going.

I was pleased with the most recent freedom of navigation operation (FONOP) on the part of the United States, and we need to continue that. We need to continue the engagement with the Japan’s Self-Defense Forces (SDF), with the Maritime Self-Defense Force in particular, with respect to preserving the international order in the South China Sea. Clearly, China continues to be very aggressive. Together – and not just Japan and the United States – but all nations in the region need to continue to engage on this issue so that China doesn’t get any kind of free pass and international law is followed.

The South China Sea is a body of water that’s available to everybody; that challenges continue to evolve as China builds out these artificial islands. We all need to continue to push very hard on addressing that so that it isn’t, China isn’t, given the space to create a new reality in the region.

Q: How much are you concerned about North Korea?

A: I worry a great deal about the continued development of nuclear weapons on the Peninsula. That’s a very difficult problem. I think it takes everybody in the region to address this, including China. I think China has to work as hard or harder than anybody else to create pressure on Kim Jong-un to back away from both the development and the potential use of nuclear weapons.

Q: You said that there is no military option for this North Korean issue. Can you elaborate on that?

A: Well, I’m not saying that. With respect to military options, they’re just very difficult. They’re very, very difficult. There are always military options, but certainly that wouldn’t be my choice. I think China really needs to push hard on additional sanctions, literally from China, as opposed to the international sanctions, which have proven to be minimally effective with respect to deterring or changing North Korean behavior.

Q: Looking at those cases of how China handles North Korea and also what they do in the South China Sea, I think it’s apparent that China does not necessarily behave as the United States and Japan want it to. What can we do?

A: I think we have to continue to press very hard in every dimension. We have to press through the United Nations, we have to press at the international law level. We have to press, literally, at the local level. We have to press through organizations like ASEAN (Association of South-East Asian Nations) or the Southeast Asian defense forum. We just can’t give an inch to China with respect to what they seemingly continue to do here.

And yet we all, including China, need to be able to do this without miscalculating and getting into a conflict. I think the economic development in the region, whether it’s Japan, America, China, the other countries, if we get to a point where we’re near conflict or we get into a conflict, that economic development dramatically drops for everybody and it hurts everybody very badly.

So, I think we, the United States, Japan and the other countries in the region, have to be very forthright with China, with respect to really understanding from them what their intentions are here, where they are going. And that, as they grow into a global power and even a regional power, they do so in a responsible way.

Otherwise, I think the word that you used earlier, “deteriorating” becomes the right word. And if the situation continues to deteriorate, then it just becomes much more dangerous.

Q: Through these meetings in Tokyo, did you find a gap in the threat perceptions between Japan and the United States? Here in Japan, there is a view that the United States may be more focused on threats from Russia than those from China.

A: Well, I think there’s a tremendous global and strategic focus right now, obviously, on Russia. But in the region we still have every bit of the Seventh Fleet here. We have thousands of United States Marines, who are stationed in Japan. We have lots of United States Air Force forces.

So while, globally, and maybe in the news and clearly what Russia has done, whether it’s Crimea, Ukraine, or now the challenges we have in Syria and the Middle East, I think those will continue, but I don’t think that focus continues at the expense of the focus here, because the regional forces, the military leadership, and the political leadership in the United States, still holds this region in great regard, at a very high priority.

Q: Did you sense concern or skepticism about the sustainability of the rebalance strategy, among those people you met here in Japan?

A: I actually haven’t seen that. I certainly have watched the U.S. President Barak Obama and his administration not just generate the rebalancing but also focus on it. I didn’t get, from any senior Japanese government officials, concern about that. I had some interaction with business leaders and that question came up.

And I think from a Japanese perspective it’s a fair question. But I didn’t sense, even as it was asked, that there were any details in terms of the rebalance that they were worried about. It was almost like there’s a lot going on in the world. The United States is a global power. But we’re able to focus on more than one thing at a time.

And I have not heard a word from any American that we are any less focused and committed to this region than we have ever been.

Q: You’re a Middle East expert, and I was wondering what the impact of the exacerbating relations between Sunni and Shia on the Asia-Pacific is.

A: I just worry a great deal that this whole issue between Saudi Arabia and Iran is a very, very serious and very dangerous issue. I don’t see Saudi Arabia and Iran are getting into a conflict at this point, but at the same time I suspect that they will intensify their efforts that they’re focused on right now. Saudi Arabia and Syria, in its own way, in Yemen, et cetera, and then Iran, clearly in Syria, as well as Lebanon and its support of terrorism, et cetera.

And all of this continues to make the Middle East boil. And when it’s boiling like this it’s very difficult to predict exactly what’s going to happen. I think the United States will continue to stay engaged, working very hard, in particular right now, on the whole ISIS issue which is a huge concern to me. And I’ve felt, for many, many years, a threat like ISIS, if we don’t deal with it there in theater in that part of the world, we’ll be facing it in the United States.

And that, then, begs the question, “How much of it, then, should we be concerned about it coming here, to this region, to Japan or to Southeast Asia?” And that’s why it’s got to be stopped.

I’m hopeful that political leaders, not just Prime Minister Abe or President Park, but political leaders globally help focus on resolution of Syria, in particular, “Where does Iraq go?” and engaging in a way where this Saudi Arabia-Iran enmity which is heightened right now simmers down considerably.

Q: Is there anything that you expect, specifically, Japan to do, in these issues in Middle East?

A: Well, I was asked about it a lot while I was here.

Hopefully, that’s a reflection of wanting to understand it and, from a political standpoint helping from a humanitarian standpoint. I certainly don’t have high expectations that there’ll be military capability coming from Japan. But oftentimes that’s not the most important; it’s the other things that we really need that kind of help and support on.

Q: You talked about the need for a heavier commitment for the operational tempo or the op tempo, to be raised in the South China Sea to deal with China. Can you elaborate on that?

A: Well, 10 years ago – when I was the head of our Navy, our Navy got smaller, coming down from the 1980s where we almost reached 600 ships to now hovering around 300. We’re actually, I think, at 280.

One of the concepts that I felt strongly about 10 years ago and still do, is this concept called “the thousand ship Navy.”

And it really met two needs. One is I don’t think we’re in a world now where the United States can do it alone, no matter how big we are. We’re living in a multipolar world. And secondly, we have relationships with maritime forces and navies all over the world.

And, in this region, whether it’s Japan, or Australia or South Korea, – I think using the totality of those capabilities together creates a balance and potentially creates a balancing factor against what China is doing in the region from a maritime standpoint.

So I would hope that the relationships would be able to focus on use of these navies at the right operational tempo, which sends China very strong messages that, “We’re just not going to tolerate where we think you’re going, which is that this is your body of water. It is not. It is everybody’s body of water.” So that’s what I meant by the specific operational tempo.

I would hope, specifically for the United States, that we would have a very upbeat freedom of navigation op tempo, particularly in these disputed areas, so that we send China a very strong message about “These are international waters and you have no more rights in them than we do,” as some of these longterm claims, whether it’s the Philippines, or Vietnam, or China, get resolved over time peacefully.

Q: Are you saying that the United States should do much more than the current administration is planning to do?

A: I don’t know what the current plan is. I was pleased the current administration actually created, or actually executed, this FONOP, this freedom of navigation op, last November. I just think we need to do it more frequently.

Q: What should and can Japan do, in terms of this freedom of navigation operation in the South China Sea, or in order to send a message to China?

A: I rarely give advice publicly to other countries. One, I think it really is up to the Japanese leadership. Secondly, in my meetings here over the course of two days there’s great focus on this, and I take away that there is a strategy and a plan that Japan has to address what the Chinese are doing.

Q: Do you think it’s a good idea for Japan to become a security provider in this region? Up until now, Japan tends to depend on the security that the United States provides. But after the conclusion of the revised Guidelines for Defense Cooperation with the United States and the recent enactment of security-related bills, there is an emerging motivation that Japan become a security provider and join the United States to maintain the regional security order. Do you think that is a good idea?

A: I’ve been impressed with how Japan has addressed these issues. The history is very difficult. I don’t have to explain that to anybody from Japan. So, I’m not surprised that there is a patient pace here, if you will.

I do think we have to, if we can, objectively look at the security environment now, versus what the security environment has been over the last 60 or 70 years and it’s changing. So, specifically, I’m very pleased at the changes that have been made to allow for the collective self-defense; that Japan can help support American forces if they’re under attack.

It’s really important that this be developed and moved by the Japanese political leadership although. I do think the security environment is changing and the more the United States and Japan can work together, the better it will be, in terms of our addressing the challenges of that environment.

Q: What’s the weakest point of the alliance?

A: One of the things that I was asked about several times while I was here was the whole issue of intelligence sharing.

Intelligence is a very, very complex area. It is for the United States, which has had it for a long time. So, I’m not saying I would say that’s the weakest but I think that’s as challenging as any part of the relationship.

And how do we do that? In the world in which we’re living, we will have to share the right information and intelligence to properly assess and address the issues.

Q: So, if Japan cannot really become a partner to the United States in terms of intelligence sharing, as the “Five Eyes” countries, is Japan still a sort of second tier ally to the United States?

A: I think that’s just too harsh. We have relationships with a couple of hundred countries globally. We obviously have unique, longstanding relationships in the intelligence world in terms of the countries that are in this “Five Eyes” relationship. I know we do have a very valuable relationship with Japan in areas that I think are also important. Where that goes in the long run, I’m just not sure.

Q: What should Japan do to advance the intel-sharing with the United States?

A: I think any country has to figure out how it securely handles its intelligence. And I’m not an intel guy, so I couldn’t give you what the track is specifically. But I do know, first of all, that there is an important relationship which over the long run is going to keep asking the question about, “How much should we share and can we share?” as we address these issues together.

Q: Finally, what’s the utility of the Military Statesman Forum (MSF), taking all those points that you have already raised into consideration?

A: Well, it does a lot of things, one of which is (that) it’s able to extend the active duty relationships we had with our counterparts into continued commitment to the relationship on both sides. Secondly, it allows – and to tap, to a great degree, the wisdom of very senior people, that have led in very difficult times. And to help the younger, the newer, generation of leaders evolve.

Secondly, it, as the whole national security structure inside Japan evolves – I mean, you’ve stood up a National Security Council, you have a National Security Staff, and this came obviously as a result of the leadership of the Abe administration. But having watched (the nuclear accident in) Fukushima and Tomodachi Operation, myself, the disorganization and disconnect inside the Japanese government, in so many ways got in the way of being able to do what needed to be done. That’s changing.

So, the United States – not that we’re perfect, believe me – but we have a structure that we’ve all dealt in, and so we can use some of what we’ve learned to inform our Japanese counterparts, and then they can figure out whether it applies or not to Japan.

The whole issue – which is very complex –of the relationship between civilian leadership and military leadership is another one that I think there is a great value in.

Q: I see.

A: So, I think it’s a great answer for how we evolve in a new security environment. And I really applaud Dr. Funabashi, (Chairman of the RJIF) and also the leadership in the government that supports it on both sides so we can continue to have these dialogues and maybe impact in a meaningful way these major challenges.

Q: The next round of MSF is coming up in July. What do you think has to be discussed?

A: We will talk about a number of things. Actually, what heads the list, for me, is this whole issue of the civilian/military relationship.

Certainly, I don’t know how we have a meeting like this without addressing the current situation in the South China Sea, China, North Korea, trilateral with the ROK, et cetera. And I think there’s this global Middle East challenge that both of us have to be informed on.

Profile

Admiral Michael Mullen

Admiral Michael “Mike” Mullen served as the 17th Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff from 2007 to 2011. He was the principal military advisor to President George W. Bush and President Barack Obama, overseeing an end to the combat mission in Iraq and the development of a new military strategy for Afghanistan. Admiral Mullen had also overseen 24,000 US servicemembers as part of Operation Tomodachi following the Great East Japan earthquake of March 2011.

After retiring on September 30, 2011, he now serves on the board of directors for General Motors and Sprint, teaches as an adjunct professor at Princeton’s Woodrow Wilson School, and is a member of the National Academy of Engineering. He also is a Regular Member of RJIF’s Japan-U.S. Military Statesmen Forum and continues to engage with the security policy communities in both the U.S. and Japan.

Admiral Mullen graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, earned a Master’s of Science degree in Operations Research from the Naval Postgraduate School, and completed the Advanced Management Program at the Harvard Business School.

Japan-U.S. Military Statesmen Forum (MSF)

MSF brings together former Chairmen of Joint Chiefs of Staff from the U.S. with former Chiefs of Staff of the Joint Staff from Japan, aiming to strengthen policy dialogues, reinforce the “bonds” (kizuna) between allies, and pass on received wisdom from retired flag officers to the active duty forces and security policy communities of both countries.

Until the first MSF meeting in 2014, there had been no direct channel for strategic dialogue between the U.S. military and the Japan Self Defense Forces. MSF seeks to enhance the U.S.-Japan Alliance by providing such a channel, as the preservation of regional security has grown more important yet has become increasingly complex. The location of each annual meeting rotates between Tokyo and Washington, D.C.

APIニュースレター 登録

APIニュースレター 登録