Limes n.9 / 2023 “La Cina resta un giallo” (October 5, 2023)

The Tyranny of Geography: Okinawa in the era of great power competition

Research Associate

Since Okinawa’s handover back to Japan in 1972, the prefecture has played an indispensable role in Japan’s national security. The reason for this points to history: the chain of islands in the southwestern part of Japan had remained under United States occupation for twenty years longer than the rest of the country. During this period, the U.S. built a number of military installations on the islands as part of their strategic force posture in the Asia-Pacific. Even upon its return to Japan, the military presence on Okinawa remains, and the islands have continued to carry a much larger burden for Japan’s defense than the other 46 prefectures.

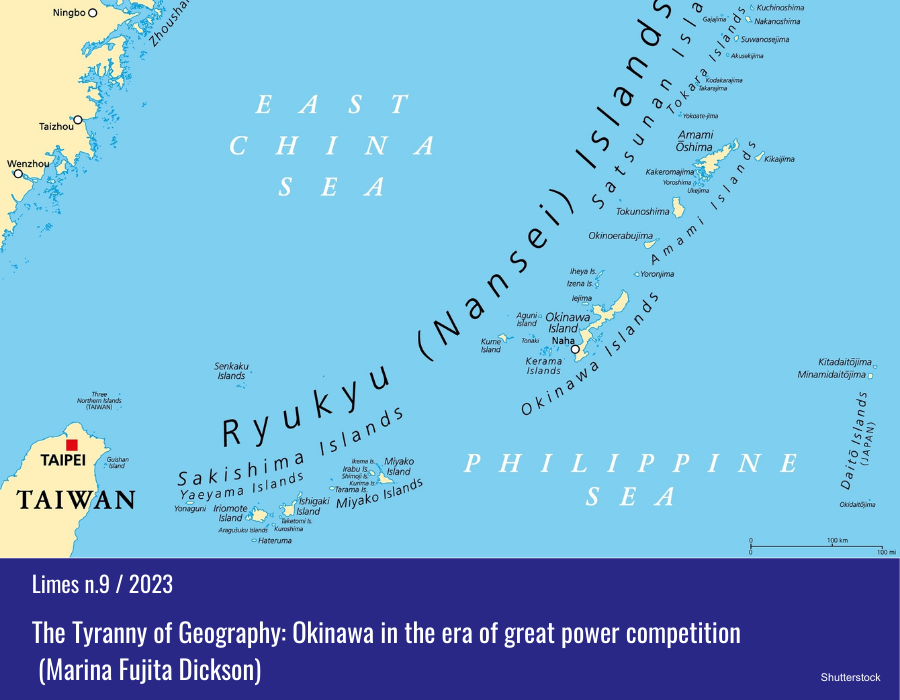

Today, Japan hosts more US military installations and American troops than any other country. Okinawa hosts 70% of these facilities, despite only being 0.6% of Japan’s total land mass. The islands host about 25,000 American soldiers in total. Located on the first island chain which extends to Taiwan and the Philippines, Okinawa is in a geographically strategic but vulnerable location, making it a focal point in the region’s geopolitical competition. Both the United States and Japan heavily rely on the bases in Okinawa for their security, and with the increasingly unstable dynamics in US-China relations, this reliance will not subside anytime soon.

Okinawa is thus caught in the middle of great powers. Given the islands’ history, this situation is not new to them, but their geographic vulnerability is mostly out of their control. For decades, the Japanese Self Defense Force (SDF) and the U.S. Military have operated their bases on the islands for deterrence against regional adversaries, and their presence has mostly been unwelcomed. Okinawa has long held heavy grievances regarding the base, but perspectives on the islands have started to diversify.

In Japan’s calculation of a Taiwan contingency, Okinawa is a unique piece. To some extent, its future rests on how its neighboring security challenges develop and whether or not U.S.-China relations will stabilize. At the same time, some Okinawans are seeing the need for military presence on their islands for their own security, given Okinawa’s proximity to Taiwan. The prefecture’s history, politics, geography, strategic importance, and vulnerability will all play into what lies ahead for Okinawa and Japan’s security.

Okinawa’s relationship with its surrounding larger powers predates its time under Japanese sovereignty. Okinawa was originally governed by the Ryukyu Kingdom, which had its own distinct language, religion, and culture. The Ryukyus had a long-standing trade relationship with China, and in the 1400s, the Ming Dynasty established a tributary relationship with the Ryukyu Kingdom.

In the 200 years that followed, the Ryukyuans flourished. Given their geographic advantage, they established trade routes beyond China to Southeast Asia. In 1609, the Satsuma invasion forced the Ryukyuans to balance their tributary relationship between Japan and China. Eventually, mounting pressure from Western countries to access the islands themselves led to Japan officially annexing the Ryukyus in 1879.

THE KEYSTONE OF THE PACIFIC

Okinawa’s geography was crucial for Japan’s national defense, which was evident at the end of World War II. During the final campaigns in the Pacific, Commander of the Allied Powers General MacArthur and Third Fleet Commander Admiral Halsey had identified Okinawa as a critical step of the island-hopping campaign to push Japan to surrender. Japan, on the other hand, used Okinawa as a buffer for the American invasion, forcing islanders to face the bloodiest battle in the Pacific where one in four Okinawans lost their lives.

In the post-war years, the bases in Okinawa, dubbed then as the “Keystone of the Pacific” proved to be crucial for the United States in helping oversee their security concerns in Asia. For example, during the Vietnam War, Kadena Air Base served as a critical transit hub where B-52s would take off en route to Southeast Asia.

However, in the twenty years between the end of the U.S. occupation of Japan and the Okinawa Agreement in 1971, American foreign policy priorities began to change. At first, the US focused on preventing Japan from post-war remilitarization and valued Okinawa as an extension of US policy goals in Asia. A 1948 National Security Council (NSC) report on the United States objectives for a peace treaty with Japan noted that the US “intends to retain, on a long-term basis, the facilities at Okinawa… as are deemed by the Joint Chiefs of Staff”, and that the U.S. would “seek international support for itself to maintain long term strategic control” of the islands [1]. Both Presidents Eisenhower and Kennedy held the position that retaining control of Okinawa “indefinitely… was strategically and militarily important” for US policy. Unlike other bases in Asia, Okinawa had nuclear weapons stationed there, and conventional forces there were critical for not only supporting operations in Vietnam but also defending South Korea and Taiwan. During the Johnson administration, however, US policymakers began to warm up to the idea of returning Okinawa to Japan. By this point, the U.S. was more interested in Japan having a greater role as a regional player and contributing more to the US-Japan alliance militarily. At the same time, the use of Okinawa’s bases for American operations in Vietnam and Cambodia began to fuel anti-US sentiment on the islands, triggering an uptick in the popularity of communists and socialists in Japanese politics. Both trends served as a warning to the Americans that the return of Okinawa needed to be definite and soon. Then Japanese Prime Minister Eisaku Sato was also under increasing pressure from the public to recover Okinawa, so by the Nixon administration, the reversion of Okinawa was not just an idea, but a policy priority for both sides.

Ultimately, the two sides were able to come to an agreement. Administrative control of Okinawa would be transferred to Japan, while the US would “retain maximum military flexibility [for their] bases” on the islands [2]. The reversion met the policy goals of both Washington and Tokyo, but of course, the islanders it would affect most had little input.

THE CHINA THREAT FOR JAPAN

In the post-war period, Japan has had to balance against three looming security challenges in its periphery: Russia, North Korea, and China. Among these, the threat of China has become exponential. Growing antagonistic activity in the East and South China Seas, sizable investments in long-range precision strike capabilities, short-mid range cruise and ballistic missiles that are well within range of striking Okinawa’s main island are all major concerns. In 2015, China’s naval fleet size overtook the U.S.’s. The PLAN (People’s Liberation Army Navy) is further expected to grow to 400 ships by 2025, with priority on surface combatants and expanding its aircraft carrier forces [3]. The U.S. and Japanese governments have acknowledged this materializing threat. In the 2022 U.S. National Defense Strategy, China was named America’s most “comprehensive and serious challenge to national security.”[4] Japan echoed this concern in its most recent 2023 Defense White Paper, naming China as its “greatest strategic challenge.”[5]

In response to this heightened threat, the US and Japan have both expanded their force posture in Okinawa, whose capital Naha is only 400 km (249 miles) from the contested Senkaku Islands, that both China and Japan claim. Also of concern is the proximity of Taiwan to Yonaguni, the far west island of Okinawa, at only 110 km. Taiwan has been identified as a “core interest” to the PRC, and Beijing has not ruled out reclaiming the island by force. Chinese military activity in the area has been putting pressure on Taiwan’s defenses, heightening concerns in both Washington and Tokyo on the possibility of an imminent invasion.

While Japan has typically advocated for the “peaceful resolution” of conflicts on the Taiwan Strait, the idea of a war erupting in Okinawa’s backyard has prompted Japanese officials to be more vocal in Taiwan’s defense. Former PM and current Vice President of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) Taro Aso said to an audience in Taipei last month that Japan must “show resolve to fight” in helping defend Taiwan [6]. At the US-Japan-ROK Trilateral Summit at Camp David in August, PM Kishida and his counterparts condemned China for its “dangerous and aggressive behavior” in the South China Sea [7].

To bolster its deterrence capabilities in the region, Japan opened a new Self Defense Force (SDF) base on Ishigaki, an island in the southwest part of Okinawa, earlier this year. Along with some 570 troops, the base will host surface-to-air missiles and Type-12 surface-to-ship missiles to deter Chinese aircraft and naval ships passing along nearby waters. While the Type-12 missiles are currently defensive in nature, they will be upgraded to reach enemy bases in the next three years to achieve Japan’s new counterstrike capability.

To further strengthen its force posture, Japan announced in its 2022 Defense Buildup Program plans to change all existing regional SDF brigades and divisions outside of Okinawa into rapid-deployment units, which will allow them to operate outside of their designated areas and concentrate combat power where needed in the event of a conflict.

GRADUAL SHIFTS IN OKINAWA’S VIEW

The expanding presence of the SDF in Okinawa has predictably been met with swift backlash. While some residents of Ishigaki saw value in having missile defense capabilities on the island, they worry the upgraded capabilities will make them an obvious target, especially in a Taiwan contingency.

The protest against the new base in Ishigaki is just the most recent of organized demonstrations in Okinawa against the armed forces. For decades, local residents have been victims of violent and petty crimes perpetuated by US soldiers stationed on the islands. In 1995, frustration swung to outrage when three U.S. marines stationed at Futenma Base kidnapped and raped a 12-year-old girl. Subsequent protests called for the US to reduce its number of troops on the island, so the Department of Defense proposed the idea of closing the Futenma base and relocating some troops to a new base on the northern end of Okinawa at Henoko. Island residents see this as an inadequate solution that does not address the issue of U.S. base presence writ large. Futenma base was scheduled to close in 2003, but with no agreed solution, is still being used today. For locals, the bases are a constant reminder that they carry the weight for the rest of the country’s national security. At times of peace, Okinawa is a buffer for the rest of Japan; in times of war, they are the first target of attack.

Okinawans’ grievances regarding the military presence in their communities remain strong even fifty years after the reversion, but local opinion is becoming more nuanced. Polling shows 70% of Okinawans believe the concentration of US bases on the islands is “unfair”, and 83% believe the bases make them a target in a time of war [8]. Overall, almost 80% of Okinawans believe that the relationship between Okinawa and the national government is “bad.”

When breaking down responses by age, however, these sentiments look more complicated. Asked if anti-base protests are futile because it is the national government’s job to decide on national defense, 39% agreed that the protests are futile [9]. Among these respondents, those aged 18~24 most believed that the protests were futile, at 55 percent.

In 2012, 74% of Okinawans said that the disproportionate base presence in Okinawa is “discriminatory”; in 2021, this number had dropped to 66%. Okinawans in their 20s and 30s are the main reason behind this downward trend, and their new political leanings were reflected in recent elections. For decades, candidates who were backed by anti-base organizations would largely sweep the ballot box, leaving few seats for any candidate backed by the nationally popular LDP. While independent candidates still hold strong in most local races, younger voters in Okinawa increasingly support LDP-backed candidates. This led to the victory of LPD-backed Satoru Chinen last year for the new mayor of Naha, Okinawa’s capital [10]. Although the support of the LDP from younger voters is also increasing nationally, with the highest birthrate in the country, Okinawa’s youth vote is particularly impactful.

The reason for Okinawa’s generational difference in opinion could be attributed to two factors: the increasingly precarious security situation around Okinawa’s waters, and history. The brutality of the Battle of Okinawa motivated anti-militarist politics among earlier generations, but younger Okinawans are more removed from this memory. While Okinawans feel they carry an unfair burden when it comes to national security, they also see the antagonistic rhetoric and behavior by China toward Taiwan as a visible and near threat. Their concern is warranted – in December of last year, the Chinese navy sent six warships, including an aircraft carrier, through the waters between Miyakojima and Okinawa’s main island for an apparent drill against the Nansei Island Chain, which includes Okinawa. China has also been challenging Japan’s administrative control of the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands, which are close to Okinawa and have strong implications for the area’s maritime security. Last year, China responded to US House Speaker Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan by conducting military drills in the surrounding waters. Among the ballistic missiles fired, several landed for the first time in Japan’s EEZ, just south of Okinawa.

Regional differences in sentiment are therefore also evident. More residents of Miyakojima (51%) and Ishigakijima (49%) who are closest to Taiwan and the Senkaku Islands believe the Japan-US security posture needs to be “strengthened” compared to residents of other islands in the prefecture [11]. The apparent variation in responses by age and location shows Okinawans’ perception of their environment is growing more nuanced.

OKINAWA IN THE US-JAPAN-CHINA TRIANGLE

Of course, the security of Okinawa itself is critical for Japan given its acute reliance on sea lines for communication. Even if China did not resort to an immediate attack on Taiwan, a naval blockade would already have severe consequences for the Nansei islands. Japan is well aware of its vulnerability in this domain: resource scarcity was both the motivation and Achilles heel of Japan’s involvement in World War II. As a nation that relies heavily on trade, Japan must consider all potential vulnerabilities surrounding Okinawa that an enemy may exploit.

Meanwhile, the US is also reviewing the value and risks of its force posture on the islands. For instance, Kadena Air Force base on Okinawa’s main island is in an acutely more vulnerable position than other US bases in Honshu. Kadena could be attacked by as many as 252 short and medium range ballistic and cruise missile launchers from China, which is more than double what could strike the fighter base in Iwakuni and seven times more than what could reach Misawa in northern Honshu [12]. Given this risk, the Department of Defense determined that a portion of the currently stationed F-15 C/D fighters should be moved to bases in Guam, Tinian, and Darwin. With the fighters more spread out, sustained tanker and bomber operations and long-term combat resilience will be more likely in the event of a war.

China, on the other hand, is continuing to develop its relationship directly with Okinawa. Due to its historical tributary relationship, Chinese officials and scholars have previously contested Japanese sovereignty over the Ryukyus. Most recently, Xi Jinping spoke about the “deep historical connection” between China and the Ryukyu Islands during a visit to the national museum [13]. Two weeks later, a TV show from Shenzen aired a special episode titled, “The Ryukyu Issue Cannot Be a Muddled Account”, featuring Okinawan activists alongside Chinese scholars where they discussed the strong ties between Ryukyu culture and the Chinese cultural sphere and how the Ryukyus changed into “present-day Okinawa.”

In the following month, China extended an official visit to Okinawa Governor Denny Tamaki. The Governor, who has been a staunch advocate for the anti-base movement, paid tribute to the Ryukyu Kingdom’s archeological site in Tongzhou, Beijing, and met with Fujian Province party officials to discuss “friendly exchanges and deepening cooperation” between the two sides through such means as tourism, expanded flight routes, and cross-cultural exchanges [14]. In a rare move, Governor Tamaki conveyed Okinawa’s independent diplomatic exchanges with China in an exclusive interview with the Global Times before his visit, where he expressed his anticipation for his trip and deepening future interactions between the two sides [15]. For Beijing, this may be an attempt to extend an olive branch directly to Okinawa for favorable relations that Tokyo would not entertain. For Okinawa, offering cultural exchanges and pragmatic cooperation may be a way to appease China to keep itself out of any conflict surrounding Taiwan.

The tensions between the U.S., Japan, and China will not subside any time soon, though Okinawa will continue to be a critical factor for Japan’s defense. Its visible vulnerability requires the reinforcement of both Japanese and American defense postures in the region. With so many competing interests in Okinawa, the local government may be limited in what it can do, but a new generation’s shifting views on defense policy are perhaps pushing Okinawa’s voice to evolve. Ultimately, this change in opinion, coupled with Japan and the United States’ ability to effectively deter a conflict in the region and successfully manage great power rivalry, will determine Okinawa’s geopolitical future.

[Note] A version of this article has been translated and edited in Italian has been published on Limes n.9/2023 “La Cina resta un giallo”

[1]U.S. National Security Council, “Recommendations with Respect to United States Policy toward Japan”, NSC 13/2, October 7 1948, p.6, U.S. Declassified Documents Online (CK2349347865)

[2]Watts, Robert C. IV (2019): “Origins of a ‘Ragged Edge’ – U.S. Ambiguity on the Senakaku’s Sovereignty”, Naval War College Review: Vol. 72: No. 3, Aritcle 8, p.114-115.

[3]Sam LaGrone, “Pentagon: Chinese Navy to Expand to 400 Ships by 2025, Growth Focused on Surface Combatants”, USNI News, November 29 2022.

[4]Department of Defense, United States National Defense Strategy, 2022, p. 4

[5]Ministry of Defense, Defense of Japan (Annual White Paper), 2023.

[6]Kantaro Komiya, “Japan ex-PM Aso’s ‘fight for Taiwan’ remark in line with official view, lawmaker says”, Reuters, August 10 2023.

[7]White House Briefing Room, “The Spirit of Camp David: Joint Statement of Japan, the Republic of Korea, and the United States”, August 18 2023.

[8]“Beigunkichi ni jakunen-sō wa kōtei-teki, Henoko isetsu `hantai’ Okinawa de medatsu… Yomiuri seronchōsa” (“Young people are positive about US military bases, ‘opposition’ to relocation to Henoko stands out in Okinawa… Yomiuri public opinion survey”), Yomiuri Shimbun, May 13 2022.

[9]“Okinawa kenmin 39-pāsento ga anpo kyōka motomeru `dochira-tomo iezu’ 37-pāsento Henoko isetsu 46-pāsento ga hitei-teki Myōjōdai kyōju-ra chōsa” (“39% of Okinawans want to strengthen security, 37% say “can’t say”, 46% say no to Henoko relocation Investigation by Meisei University professors”), Yahoo News, June 6 2023.

[10]“Naha shichō-sen, sedai-betsu no tōhyō-saki wa? Tōsen shita Chinen-shi wa jakunen-sō ni shintō, Tamaki chiji shiji-sō mo ichibu torikomu honshi deguchi chōsa” (“How did different generations vote in the Naha mayoral election? Elected Mr. Chinen captures younger generation and some of Governor Tamaki’s supporters, according to this Ryukyu Shimpo’s exit poll”), Ryukyu Shimpo, October 25 2022.

[11]“Okinawa kenmin 39-pāsento ga anpo kyōka motomeru `dochira-tomo iezu’ 37-pāsento Henoko isetsu 46-pāsento ga hitei-teki Myōjōdai kyōju-ra chōsa” (“39% of Okinawans demand stronger security, 37% are “undecided”, 46% are negative about Henoko relocation, research by Meisei University professors”), Yahoo News, June 6 2022.

[12]Eric Heginbotham, et al. “Chinese Attacks on U.S. Air Bases in Asia: An Assessment of Relative Capabilities, 1996–2017”, RAND Corporation, 2015.

[13] Katsuji Nakazawa, “Analysis: Xi throws Okinawa into East Asia geopolitical cocktail”, Nikkei Asia Review, 15 June 2023.

[14]“Zhou Zuyi meets with Tamaki Denny, Governor of Okinawa Prefecture, Japan”, Fujian Daily, July 7 2023.

[15]Xing Xiojing, “Exclusive: Okinawa must never again become a battlefield, says Okinawan Governor Denny Tamaki”, Global Times, July 2 2023.

Author

Marina Fujita Dickson

Research Associate

U.S. security policy / Disinformation / Japan-Korea relations / Cyber security

APIニュースレター 登録

APIニュースレター 登録