“API Geoeconomic Briefing” is a weekly analysis of significant geopolitical and geoeconomic developments that precede the post-pandemic world. The briefing is written by experts at Asia Pacific Initiative (API) and includes an assessment of burgeoning trends in international politics and economics and the possible impact on Japan’s national interests and strategic response. (Editor-in-chief: Dr. HOSOYA Yuichi, Research Director, API; Professor, Faculty of Law, Keio University; Visiting Fellow, Downing College, University of Cambridge)

This article was posted to the Japan Times on March 28, 2022:

API Geoeconomic Briefing

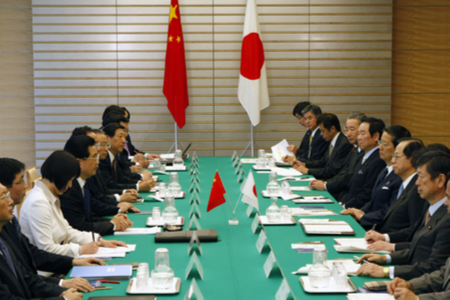

Photo: Reuters/Aflo

March 28, 2022

Initiating dialogue on universal values is essential for Japan and China

OIKAWA Junko

Associate Professor, Chuo University.jpg)

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has made clear the global challenges the international community faces.

Can the international society restore peace — a universal value common to all humankind — amid rising geopolitical risks? And can it implement effective efforts to protect human rights and the rule of law?

In 1972, Japan and China normalized diplomatic relations, despite differences in their political and social systems and ideologies, ending what was still technically the state of war between the two nations.

After many twists and turns, Japan and China, even 50 years after normalizing ties, are still only halfway down the road to improving their relationship.

However, it is our common understanding that their relations are important not only in a bilateral context but also because of their enormous clout on peace and stability in the Asia-Pacific region and the world.

As efforts to reconstruct international order are underway, Japan and China must avoid conflicts of interest and further develop their relationship through a so-called strategic choice approach, or seeking common interests and building consensus.

The global community is now shifting to a structure in which countries compete over the superiority of their political and social systems — democracy or authoritarianism. Confrontations over values that lie behind the rivalry between different systems are becoming more prominent.

A typical example is the difference in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. While both democratic and authoritarian regimes share the value of protecting people’s lives and health, there is a greater discrepancy over the extent of limitation to individual rights and social stability.

The Chinese Communist Party’s authoritarian rule has had a great impact on the global community, establishing its own governance model that makes use of the world’s most advanced digital technology. Conflicts over “universal values” have become an important issue in discussing China.

Is it possible for Japan and China to deepen dialogue on such universal values as peace, freedom, equality, democracy, human rights and rule of law?

I would like to re-evaluate the historical achievements of the two countries, made possible through consensus building based on strategic choices, and reconsider their common interests in the context of universal values.

As Chinese President Xi Jinping’s administration tightens its control on freedom of speech and thought, it goes without saying that it would be difficult to discuss universal values. But I believe it is necessary to view China from a multifaceted perspective, not only criticizing its authoritarianism but also understanding the diversity and complexity of Chinese society.

50 years of strategic choices

Ties between Japan and China are complex and multilayered, made up of political tensions, economic interdependence and a relationship of influencing one another historically and culturally.

Geopolitically, the two countries and their surrounding areas are facing mounting national security challenges.

Amid such circumstances, the two sought common interests and continued to make strategic choices. Their footsteps are embodied in the “four basic documents” that served as the basis for their relations: the 1972 joint statement; the 1978 peace and friendship treaty; the 1998 joint declaration; and a joint statement in 2008.

The Japan-China joint statement of 1972 stated that in spite of the differences in their social systems existing between the two countries, the nations should, and can, establish relations of peace and friendship.

The peace and friendship treaty of 1978 said that the two nations should settle all disputes by peaceful means and neither should seek hegemony.

The normalization of relations came during the Cold War amid U.S. rapprochement with China to counter the Soviet Union.

The Japanese public had increasingly been pushing for a shift in Japan’s policies towards China. Therefore, improving ties with China, which had been going through its Cultural Revolution, largely worked to the advantage of both parties.

The two nations strategically chose peace, friendship and non-hegemonic relations as important common interests.

The joint declaration of 1998 is formally called the Japan-China Joint Declaration on Building a Partnership of Friendship and Cooperation for Peace and Development. In the declaration, both sides shared the view that under the current situation in the post-Cold War era, strengthening cooperative relations between the two countries contributes to the peace and development of the Asia-Pacific region and the world as a whole.

Among the four documents, perhaps the most important is the 2008 joint statement on the comprehensive promotion of a “mutually beneficial relationship based on common strategic interests.”

Regarding the enhancement of mutual trust in the area of politics, the two countries stated that they are resolved “to engage in close cooperation to develop greater understanding and pursuit of basic and universal values that are commonly accepted by the international community.”

At that time, there were active interactions between Japan’s leaders and then-Chinese President Hu Jintao and then-Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao. It was epoch-making that the term “universal values” was mentioned in a political document between the two countries.

After that, relations deteriorated following an incident in 2010 in which a Chinese fishing boat and Japanese Coast Guard patrol ships collided in waters near the disputed Senkaku Islands.

Domestic and international situations have changed for both countries, and I would say that the “mutually beneficial relationship based on common strategic interests” between them has become a mere facade.

However, the basic documents signed by Japan and China — a result of the two seeking common interests and making strategic choices for building a consensus to some extent — are their historic assets.

As the two countries mark 50 years since the normalization of ties, it is possible to reassess the principles for Sino-Japanese relations written in the four basic documents, particularly the significance of the strategic relationship of mutual benefit.

Chinese values

One of the reasons behind the rising anti-China sentiment in Japanese public polls must be, in addition to conflicts of interests between the two countries, the Japanese people’s feeling of incompatibility with and rejection toward the values promoted by the Xi administration.

While the two countries share the culture of using Chinese characters for writing, the meaning and interpretation of those characters differ. For instance, the word “human rights” is written as 人権 in both countries, but when speaking of human rights, the two countries prioritize different aspects.

Currently, China’s Communist Party-led regime is implementing ideological tightening under the “Xi Jinping thought on socialism with Chinese characteristics for a new era,” commonly referred to as the “Xi Jinping thought.” The term was first mentioned in Xi’s speech at the party’s 19th National Congress in October 2017.

It upholds “core socialist values” as the official ideology made up of the national values of “prosperity, democracy, civility and harmony”; the social values of “freedom, equality, justice and the rule of law”; and the individual values of “patriotism, dedication, integrity and friendship.”

Values such as democracy and freedom appear to be synonymous with universal values, but what was more important in Xi’s speech was the first part, in which he spoke about seeking happiness for the Chinese people and rejuvenation for the Chinese nation, building a moderately prosperous society in all respects and, above all, the party being the highest force exercising overall leadership over all areas of endeavor in every part of the country.

While the Xi administration has propagated the core socialist values within the country, it has stressed the “common values of the whole mankind” toward the global community and the need to build a “community of shared mankind destiny.”

In a speech delivered at the 70th session of the United Nations General Assembly in September 2015, Xi said, “Peace, development, equity, justice, democracy and freedom are common values of all mankind and the lofty goals of the United Nations,” while declaring that China would continue to contribute to world peace and development following the principles of the U.N. Charter.

When Xi spoke on peace, development, fairness, justice, democracy and freedom, what was his intention in describing them not as universal values but as common values of all mankind?

He apparently tried to establish consistency between the common values of all mankind directed towards the international community and the core socialist values directed towards people in China. At the same time, he must be thinking strategically about taking the lead with his own values to counter Western universal values in an increasingly multipolarized global community.

The current situation in Ukraine is making the international community reflect on the issue of peace.

China has stressed that the sovereignty and territorial integrity of any country should be respected and safeguarded, and has highlighted the urgent need for a diplomatic solution to the Ukraine crisis. But it abstained from the vote on a resolution that deplored Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine at both the U.N. Security Council and General Assembly.

Meanwhile, in February, five Chinese academics posted an open letter on the WeChat social media platform calling on the Russian government and Russian President Vladimir Putin to halt the war against Ukraine.

While it was noteworthy that such voices arose from China’s private sector, different from the party and the government, we should also be aware that the text was later deleted by authorities.

The situation of the statement going viral on social media and then being censored indicates that the voices of the private sector do exist deep inside Chinese society like an underground water vein, indicating the society’s diversity and complexity.

Dialogue on universal values

In the joint statement signed in 2008, Japan and China agreed to “engage in close cooperation to develop greater understanding and pursuit of basic and universal values.” But is it possible to conduct a dialogue based on this agreement?

Although it is not easy to understand and pursue universal values, it is necessary to reconfirm that close cooperation is a strategic choice to make in order to share common interests.

A tip for starting a dialogue would be to substantiate the abstract concept of universal values to make it more concrete.

Japan and China have common social challenges, facing global issues including the COVID-19 pandemic and the Ukraine crisis as well as domestic issues such as a low birthrate and an aging population. They share the foundations to start a dialogue on universal values, sharing common interests including peace, security and development.

But we must note that discussions over values could be criticized as interference in one another’s internal affairs.

The Beijing Winter Olympics was hit by a flurry of diplomatic boycotts from countries that accused China of human rights abuses.

In February, Japan’s House of Representatives adopted a rare resolution expressing concern over the human rights situations in China’s Xinjiang region and other areas, and China strongly protested the motion.

Ever since the 1989 crackdown on demonstrators at Tiananmen Square in Beijing, human rights have been an important factor in Japan’s China policy, and the issue is drawing attention also from the perspective of economic security in recent years.

However, it is hard to say that the discussions on universal values including human rights are shared widely and are deepened among the Japanese public.

Dialogue on universal values should be based on self-reflection and mutual complementation.

In thinking about the situation in Ukraine, human rights in China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region and democracy in Hong Kong, what is challenged is the maturity of Japan’s civil society.

After 50 years of normalizing ties, Japan and China need to contribute further to world peace.

They must continue a dialogue, discussing rights and wrongs forthright as “zhengyou,” meaning critical friend, break away from conflicts of interest and Cold War mentality, and accumulate strategic choices to seek common interests.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this API Geoeconomic Briefing do not necessarily reflect those of the API, the API Institute of Geoeconomic Studies or any other organizations to which the author belongs.

APIニュースレター 登録

APIニュースレター 登録