“API Geoeconomic Briefing” is a weekly analysis of significant geopolitical and geoeconomic developments that precede the post-pandemic world. The briefing is written by experts at Asia Pacific Initiative (API) and includes an assessment of burgeoning trends in international politics and economics and the possible impact on Japan’s national interests and strategic response. (Editor-in-chief: Dr. HOSOYA Yuichi, Research Director, API; Professor, Faculty of Law, Keio University; Visiting Fellow, Downing College, University of Cambridge)

This article was posted to the Japan Times on March 7, 2022:

API Geoeconomic Briefing

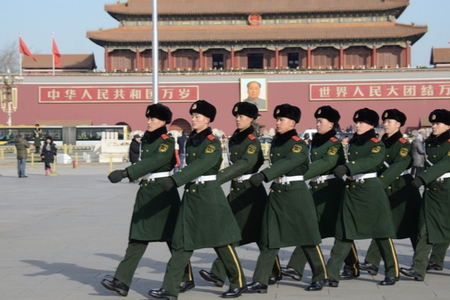

Photo:Shutterstock

March 7, 2022

Untangling the roots of the instability in Japan and China’s relationship

ANAMI Yusuke

Professor, Tohoku University’s Graduate School of Law

While Japan and China mark the 50th anniversary of the normalization of diplomatic ties this year, military tensions between the two countries are rising at a time when both are becoming more economically interdependent.

Such a situation is making it difficult for the two nations to manage bilateral relations comprehensively, making their future uncertain.

The main factor behind the increasing military tensions between them is Beijing’s military expansion that has been ongoing for more than three decades.

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP), which has had a monopoly on power in the country for more than 70 years, has invested a huge amount of money since the 1990s in the massive overhaul of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), expanding its activities to the East China Sea, the South China Sea, the Western Pacific and toward the Indian Ocean.

In the East China Sea, the PLA’s military vessels and aircraft are expanding their operations to Japan’s coastal waters, and the ships of the China Coast Guard — a part of the People’s Armed Police operating under the command of the Communist Party’s Central Military Commission, just like the PLA — are repeatedly entering Japan’s territorial waters near the Senkaku Islands.

In the South China Sea, the PLA has conducted reclamation work on several reefs scattered across the Spratly Islands and constructed military installations, leading to escalated military tensions with nearby countries such as Vietnam and the Philippines.

In the face of such actions by China, Japan has ramped up the defense of its remote islands, while advocating its “Free and Open Indo-Pacific Strategy” and stressing the importance of maintaining a rules-based maritime order.

Meanwhile, the United States, an ally of Japan, is no longer ignoring the PLA’s attempts to change the status quo, taking various countermeasures including:

- Strengthening its alliance with Japan.

- Adopting the Pivot to Asia strategy.

- Deploying more troops to the Asia-Pacific region.

- Conducting freedom of navigation operations in the South China Sea.

- Reviewing its policy of engagement with Beijing.

- Launching multilateral frameworks such as “the Quad” with Japan, Australia and India, and the AUKUS security agreement with the United Kingdom and Australia.

Japan’s dilemma of China being both an important economic partner and a national security threat is shared with the U.S., India, Australia, Vietnam and the Philippines.

Confrontations in the 1950s

Because the confrontation between Beijing and the U.S.-Japan alliance over security in the Asia-Pacific region intensified in the 1990s, some people regard this as a new issue that emerged along with China’s economic growth and increased military power.

However, we need to go back further, to the 1950s, to see how the confrontation began.

Immediately following the end of World War II in August 1945, a civil war resumed in China between the CCP and the Nationalist Party, or Kuomintang. The PLA, with large-scale support from the Soviet Union, drove the Nationalist forces, which could only get limited support from the U.S., out of mainland China.

The U.S. at the time was clearly trying to avoid getting deeply involved in the Chinese civil war. After the remnants of the Nationalist forces retreated to Taiwan in 1949, then-U.S. President Harry Truman announced in January 1950 that the U.S. would not engage in any intervention in Taiwan Strait disputes.

It seemed only a matter of time before the PLA would take over Taiwan if it had powerful naval and air forces with aid from the Soviet Union.

However, in June 1950, the Korean War broke out and the U.S. completely changed its course.

Based on the recognition that communist forces led by the Soviet Union were taking the offensive in East Asia, the U.S. deployed troops to the Korean Peninsula and Truman ordered the U.S. Seventh Fleet to the Taiwan Strait to protect Taiwan from a possible communist invasion.

In December 1954, the U.S. signed a mutual defense treaty with the Nationalist Party’s administration of the Republic of China (ROC) — Taiwan’s formal name.

In this way, the Chinese civil war became incorporated into the Cold War system and the situation of the People’s Republic of China — China’s formal name — and the ROC existing as two Chinas separated by the Taiwan Strait became the status quo.

The CCP tried to break the status quo throughout the 1950s but failed to gain the full support of the Soviet Union, which feared a backlash from the U.S.

Differences in the stance regarding Taiwan became one of the factors that led to the rapid deterioration of Sino-Soviet relations in the 1960s, and the U.S. took advantage of that and moved to improve its relationship with China.

In 1979, the U.S. and China established diplomatic relations. The normalization of diplomatic ties between Japan and China in 1972 was also realized in this context.

In normalizing relations with China, Japan and the U.S. severed formal diplomatic ties with Taiwan. But with the U.S. Congress having passed the Taiwan Relations Act in 1979, the country continued to have some responsibility for Taiwan’s security.

China, which had been worried that reunification with Taiwan would never be fulfilled and the civil war would be unfinished as long as the U.S. remained committed to Taiwan’s security, faced another challenge in the 1990s — Taiwanese nationalism that emerged with democratization within the island in the 1980s.

Taiwan Strait crisis

The CCP’s leaders, who feared that Taiwan would go off the path to reunification and move toward independence, tried to check and threaten Taiwanese public opinion by repeatedly carrying out large-scale military exercises in the Taiwan Strait in 1995 and 1996.

However, as the U.S. deployed two aircraft carriers to East Asian waters, the PLA, whose naval and air forces were seen as being obsolete, had to stop the exercises in the Taiwan Strait.

The 1995-1996 Taiwan Strait Crisis which put the U.S.-China tensions on a hair trigger made the CCP leaders recognize the fact that the security structure on the Taiwan Strait had not changed since the 1950s and that in order to reunify Taiwan, Beijing needs to have a military capability strong enough to counter the U.S. Navy in the waters near Taiwan.

Such a recognition has been an important driving force for China’s military buildup to date.

Other factors that led the CCP to enhance its military power included the political uncertainties following the 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown, heightened vigilance against the U.S. amid the 1991 Gulf War and their paranoid belief in Western conspiracies amplified by the collapse of communist regimes in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union.

And the Taiwan Strait crisis in the mid-1990s determined China’s course of military expansion with a focus on strengthening the navy and the air force.

To hamper Taiwan’s route to independence, it is necessary to cut the U.S. Navy’s access to the Taiwan Strait, and in order to do so, China needs to have command of the seas and the air over the waters around Taiwan, namely the East and South China seas.

Under its anti-access/area-denial strategy, China has pushed to largely boost the PLA’s naval and air forces and increase its presence in the East and South China seas since the 1990s.

And such moves resulted in continuing tensions in the seas, particularly around the Senkaku Islands and the Spratly Islands.

China’s provocative actions inevitably prompted Japan and the U.S. to cope with the issue, starting to construct a cooperative framework for Taiwan contingency in the 1990s and setting the peaceful resolution of issues concerning the Taiwan Strait as one of their common strategic objectives since 2005.

Economic growth

Generally speaking, cross-strait issues, which have the aspect of unfinished or extended civil war between China and Taiwan, can be regarded as an old powder keg of Sino-U.S. and Japan-China relations.

And China’s military buildup over the years ignited the fuse to that powder keg, leading to today’s uncertainties regarding those relationships.

The reason why the CCP has been able to continue boosting the PLA’s capabilities for more than 30 years is clear. It is because the country’s economy has kept growing for the past 30 years.

Needless to say, loans, investments and technological aid from Japan, the U.S. and Europe have contributed greatly to China’s economic growth.

This indicates that China’s continued large-scale military buildup has been made possible by companies in industrialized countries rushing to make inroads into China, turning the country into the “world’s factory,” and the markets of Japan, the U.S. and Europe importing huge amounts of products from the country.

In other words, the China-Japan and U.S.-China relations comprise a structural contradiction of deepening economic interdependence bringing about increased military tensions.

To begin with, Japan, the U.S. and Europe incorporated China into the global economic system in the hope that economic interdependence would lead to eased tensions with Beijing and to system transformation in the country. But the situation is developing in a completely opposite direction.

We cannot ignore the aspect of unfinished civil war in explaining the development.

Until now, Japan and the U.S. have adopted a makeshift policy of responding to China’s military expansion with military measures, while maintaining business relationships with the country.

However, as long as the industries of Japan, the U.S. and Europe keep on nourishing the Chinese economy, those countries will never be able to get to the roots of their tensions with China and will be forced to continue spending more on makeshift measures.

Economic sanctions

We also cannot overlook the fact that the Chinese government has been imposing economic sanctions frequently in recent years on countries confronting China regarding diplomatic or security issues, taking advantage of economic interdependence.

A typical example is when China cut off exports of rare earths to Japan in 2010 following the arrest of the captain of a Chinese fishing boat that Tokyo accused of colliding with Japan Coast Guard patrol ships off the Senkaku Islands.

In short, Japanese companies’ businesses in China are increasingly taking on the characteristics of a risk factor for Japan’s national security, as they are becoming a source of funds for Beijing’s military buildup and also an Achilles’ heel for Tokyo’s China policy.

As Japan works on revising its national security strategy for the first time since 2013, it cannot avoid facing the challenge of creating comprehensive countermeasures, fully taking into account the risks brought about by China’s military expansion, which is likely to continue for some time.

In tackling this important challenge, we have to watch carefully how much the government will look into the unfinished civil war and the structural contradiction of economy and national security in its relations with China.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this API Geoeconomic Briefing do not necessarily reflect those of the API, the API Institute of Geoeconomic Studies or any other organizations to which the author belongs

APIニュースレター 登録

APIニュースレター 登録