“API GeoEconomic Briefing” is a weekly analysis of significant geopolitical and geoeconomic developments in the post-pandemic world. The briefing is written by experts at Asia Pacific Initiative (API) and includes an assessment of burgeoning trends in international politics and economics and the possible impact on Japan’s national interests and strategic response. (Editor-in-chief: Dr. HOSOYA Yuichi, Research Director, API & Professor, Faculty of Law, Keio University)

This article was posted to the Japan Times on February 20, 2021:

https://www.japantimes.co.jp/opinion/2021/02/20/commentary/world-commentary/api-australia-china/

API Geoeconomic Briefing

February 20, 2021

Australia and Japan’s alliance can beat China’s interdependence trap

TERADA Takashi,

Professor of International Relations, Department of Political Science, Doshisha University

Despite Europe’s record of regional integration having been recently tarnished by Brexit, the Franco-German partnership — a response to the massive numbers of casualties sustained during the world wars — has been pivotal for the process toward that integration. Their shared vision of achieving lasting peace in the region is a key motivation behind their joint effort to promote European integration.

But what about the Asia-Pacific region? It has only a short history of regional integration compared with Europe, but its parallel with the Franco-German relationship is the partnership developed between Japan and Australia, the former war enemies whose relations are now classed as a “Special Strategic Partnership” involving a bilateral free trade agreement (FTA) and a defense pact.

Looking back, Japan made moves toward a partnership with Australia in 1967, when Foreign Minister Takeo Miki advocated his abortive “Asia-Pacific Policy,” and in 1979 when Prime Minister Masayoshi Ohira proposed the Pacific Rim Cooperation Concept.

The two countries worked closely together to establish the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum in 1989. During Prime Minister John Howard’s administration (1996-2007), when Australia was struggling to maintain good relations with members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) due in part to East Timor’s move for independence from Indonesia, it was Japan which created a foundation for Australia to become a member of the East Asia community.

Between 2001 and 2007, under the administrations of Prime Ministers Junichiro Koizumi and Shinzo Abe, Japan advocated the concept of ASEAN Plus Six to expand the East Asian region, enabling Australia to cooperate with Japan in frameworks such as the East Asia Summit and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (RCEP) up to the present day.

More recently, after U.S. President Donald Trump withdrew the United States from the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement (TPP) in 2017, Australia consistently supported Japan in its diplomatic efforts to rebuild the framework as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), a TPP without the United States.

For Japan, Australia is the only country which shares the values of democracy and rule of law, enjoys trade complementarity, maintains strong ties with the U.S. as a close ally and benefits most from peace and growth in East Asia.

Without the two nations’ partnership, which has lasted for the past half a century, it would not have been possible for the Asia-Pacific region to build the regional architecture of today with its aim of stability and prosperity.

Australia, Japan’s irreplaceable diplomatic partner, is currently struggling through a trade war with China, with Beijing having suspended imports of major Australian products. Relations between the two countries have rapidly deteriorated.

The clash started after Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison said on April 23, following the spread of COVID-19 infections, “We will need an independent inquiry that looks at what has occurred” in Wuhan, China. His remark led to a strong backlash in China, which feared that it could bring about a worldwide wave of lawsuits seeking compensation.

The Chinese government sent to commodities traders a blacklist of items subject to import restrictions which included at least seven products from Australia — coal, barley, copper ore and concentrate, sugar, timber, wine and lobster. This is equivalent to about 7%, or 27.15 billion Australian dollars (about ¥2 trillion), of Australia’s total goods exports excluding services in fiscal 2019, which ended in June.

Heavy reliance on China

As a result, China’s imports of Australian copper concentrate, which was more than 110,000 tons in December 2019, dropped to zero a year later. In November, some 21 tons of live lobsters were stranded at an airport in Shanghai, forcing Australian exporters to completely suspend shipments to China.

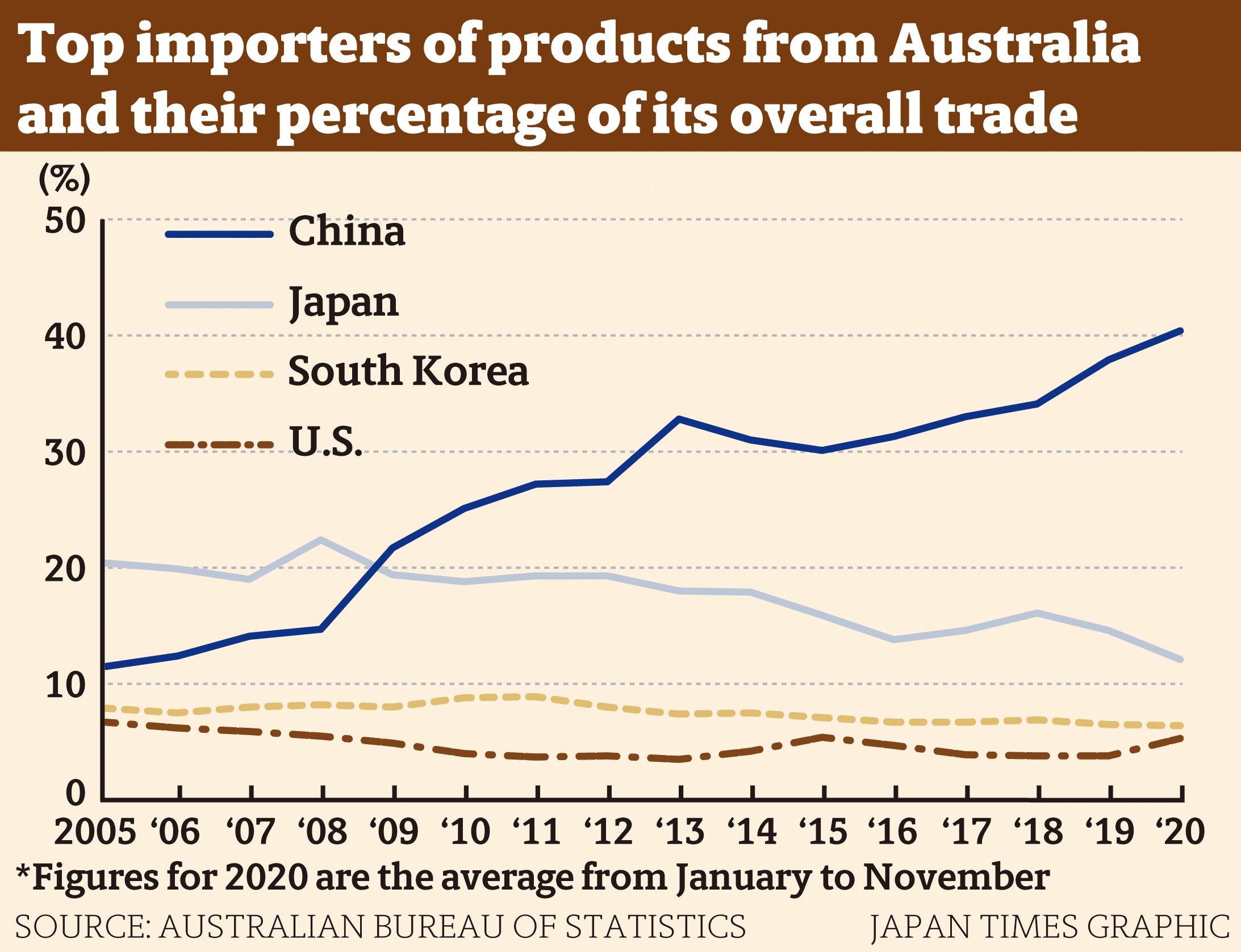

China’s import restriction measures hit the Australian economy hard in a short period of time because of Australia’s heavy reliance on the Chinese market, with China’s share of Australian exports topping more than 40%.

While Australia has been nurturing its partnership with Japan in the areas of defense, politics and diplomacy, it has looked to the rapidly growing Chinese market to boost its own economy in the last decade.

“We must enhance international supply chains’ dependence on China and develop powerful retaliation and deterrence capabilities against supply cutoffs by foreign parties,” Chinese President Xi Jinping said last year.

His remarks reflect the fact that China, which has now become the largest trading partner to more than 130 nations in the world, is in a position to exert influence for its own political and strategic interests by using its vast market power.

This means that trade dependence on China, as it deepens, is creating an environment for China to realize its national interests. It will become difficult for countries that rely economically on China to criticize Beijing’s political and diplomatic policies, as China doesn’t hesitate to threaten its trading partners even if it means a decline in economic dependence. This can be called China’s interdependence trap.

Australia’s dependence on the Chinese market increased sharply after the 2008 global financial crisis. Back then, much of China’s economic stimulus measures totaling 4 trillion yuan (about ¥60 trillion at the time) was used to improve the nation’s infrastructure, which led to a massive increase in demand for natural resources.

In fiscal 2010, Australia’s exports of mineral resources rose about 30% from the previous year to AU$170 billion (¥14 trillion), with China-bound shipments occupying 25% of total exports.

Since then, Australia continued to rely more heavily on the Chinese market, effectively letting China change the country into a partner that supports its economic diplomacy.

In November 2014, Xi and Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott met on the sidelines of the Group of 20 summit in Brisbane and agreed on upgrading the bilateral relations to a “Comprehensive Strategic Partnership.” In March the following year, Australia decided to join the China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) as a founding member, and the China-Australia FTA entered into force in December the same year. Symbolically, China made a rare commitment in the trade pact, allowing Australian medical service suppliers to establish wholly-owned hospitals and elder care institutions in many areas of China.

Australia’s inclination toward China differs largely from the stance taken by Japan and the U.S., which decided not to join the AIIB, have not been engaged in negotiations with China for a bilateral FTA and have not granted China a market economy status.

China’s political intentions

It is significant that all those moves by Australia were taken not when the Australian Labor Party, which tended to attach more importance to relationship with China, was in power between 2007 and 2013, but under the conservative Abbott administration which strengthened relations with Japan in the area of defense and security.

From China’s standpoint, it is beneficial to exert influence over Australia using a dependent trade relationship because Australia is part of the U.S.’ hub-and-spokes system — a network of bilateral alliances in East Asia. More specifically, China’s political intention behind strengthening its partnership with Australia must have been to restrain Australia’s involvement in the South China Sea disputes.

However, Australia did not go as far as supporting China by giving up its values, especially the rule of law. In July 2016, when an international tribunal in The Hague ruled that there was no legal basis to China’s claim to sovereignty over much of the South China Sea, Australia called on Beijing to respect the ruling, keeping pace with Japan and the U.S.

But after that, the relationship between Australia and China began to destabilize.

China’s frustration was reflected in an op-ed published at the time by the Global Times, the English language media organ of the Chinese Communist Party. “Australia has inked a free trade agreement with China, its biggest trading partner, which makes its move of disturbing the South China Sea waters surprising to many,” it read.

“Australia’s power means nothing compared to the security of China,” it went on. “Australia is not even a ‘paper tiger,’ it’s only a ‘paper cat’ at best.”

The bilateral relationship became increasingly icy in August 2018 after the administration of Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull decided to exclude Chinese companies, like Huawei, from participation in Australia’s next-generation 5G telecommunications network, following a similar decision from the U.S.

The one who played a key role in making the decision was Morrison, who was serving as treasurer and acting home affairs minister at the time. Morrison may well have been regarded in China with caution since then, even before he called for an independent investigation into the origins of COVID-19 after he became prime minister.

On the other hand, China is also heavily dependent on Australia in importing resources, which means China’s possible use of an interdependence trap can be a double-edged sword. For instance, China imports more than 80% of its total iron ore needs, with Australian products accounting for 65% of shipments from abroad.

There are voices within Australia calling for countermeasures against China by placing tariffs on iron ore exports, and the Global Times has reported on such calls, indicating that China is also closely watching how Australia will react next.

We should pay attention to whether this will have any impact on China in terms of changing its hard-line stance. However, such countermeasures, even if they were to be approved by the World Trade Organization, could further worsen Australia’s relations with China, and some Australian exporters to China insist that Australia should avoid taking actions that could result in losing its key position in the Chinese market in the long term.

This is a solid example of how China’s interdependence trap manifests itself — even if Australia wanted to retaliate through legitimate means within the global trade order, its dependence on China can fundamentally shift the parameters of actions it can take in its self-interest.

In December, Australia launched a formal appeal to the WTO over the 80% tariff China had unilaterally imposed on Australian barley, requesting bilateral consultations. But the situation does not appear to have progressed, with many expressing concerns that the appeal could lead to prolonged conflicts.

In order to reduce its dependence on China in the short term, it is more effective for Australia to diversify its exporting directions by utilizing FTAs with mega-markets that have more trade diversion effects — namely an FTA with Indonesia that took effect last year, a bilateral comprehensive economic cooperation agreement with India which Morrison and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi last year agreed to re-engage in negotiations, and the expansion of the membership of the CPTPP.

In the medium term, it is necessary to embody the Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP) vision in the area of trade and further expand and deepen the CPTPP which achieves high-level liberalization and maintains key functions as a key economic rule-setter. It is encouraging that the U.K.-Japan bilateral FTA, which came into effect on Jan. 1, serves as a key step toward the United Kingdom’s involvement in the CPTPP, and that the U.K. now actively supports the FOIP concept.

Xi, in his remarks at the APEC leaders’ summit on Nov. 20, said China “will favorably consider joining the CPTPP,” prompting the world to calculate his real intentions and the possibility of China taking part in the framework. This may open the way for Australia to get out of China’s interdependence trap.

CPTPP offers route forward

Countries wishing to join the framework need to enter pre-negotiations with CPTPP members on a bilateral basis. This will provide an opportunity for Australia to directly demand China to withdraw its hefty tariffs on Australian products. If China refuses the requests, Australia can legally express opposition to China’s participation.

Should this occur, it would be desirable for Japan to support Australia’s requests and decisions as a country that shares the common value of rule of law respected at the WTO.

The CPTPP can become a foundation for realizing the FOIP vision, as it incorporates various provisions that ask for freedom and openness, such as prohibiting requirements for transfer or access to the source code of computer software and securing transparency in state-owned enterprises. Such provisions are not included in the RCEP regarded to be led by China.

As Japan advocates as its diplomatic goal the FOIP vision which is not supported by China, expanding the CPTPP’s membership and enhancing its rules will become an effective diplomatic tool not only for Australia but also for Japan, which was hit by China’s rare earth metal export ban in 2010 but still depends on China for about 60% of its imports.

CPTPP’s promised liberalization with high-standard rules in trade and investment, which can lead to deeper economic interdependence among like-minded states, is effective for reducing member states’ trade dependence on China and their vulnerability arising from trade and investment reliance on the Chinese market. To maximize the effect of the CPTPP’s influence on China, it is indispensable for the administration of U.S. President Joe Biden to return to the deal.

The success of the Japan-Australia “economic alliance,” which can be compared to the Franco-German partnership in integrating Europe, very much depends on whether the two nations can work together to bring the United States back to the CPTPP, a key step toward the realization of the FOIP vision.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this API Geoeconomic Briefing do not necessarily reflect those of the API, the API Institute of Geoeconomic Studies or any other organizations to which the author belongs.

APIニュースレター 登録

APIニュースレター 登録