IOG Economic Intelligence Report (Vol. 3 No. 17)

The latest regulatory developments on economic security & geoeconomics

“China Week” Next Month in the House: The U.S. House of Representatives is scheduling a series of votes on legislation related to China sometime in September, including measures addressing the de minimis threshold and outbound investment. Speaker of the House Mike Johnson (R-LA) said at the Hudson Institute in July that “The House will be voting on a series of bills to empower the next administration to hit our enemies’ economies on day one. We’ll build our sanctions package, punish the Chinese military firms that provide material support to Russia and Iran, and we’ll consider options to restrict outbound investments”.

Specific bills include a measure to build on the Biden administration’s Executive Order “Addressing United States Investments in Certain National Security Technologies and Products in Countries of Concern” by restricting outbound investment and a measure to reform the de minimis threshold (a limit on the value of imports eligible for tariffs, and governs which products manufactured outside the United States but incorporating U.S. content fall within the purview of U.S. export control law) which currently allow imports under $800 to enter the United States duty-free. The legislation proposed by Senator Ron Wyden (D-OR), chair of the Senate Finance Committee with jurisdiction over trade issues, would target “fast-fashion” imports by excluding items such as textiles and apparel from the duty-free General System of Preferences (GSP) program. The Treasury Department, which has jurisdiction over de minimis, is also expected to issue a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking in the coming weeks.

Application Denied: The United States rejected Vietnam’s appeal for “market economy” status after a year-long review, citing “the extensive government involvement in Vietnam’s economy [that] distorts Vietnamese prices and costs.” Vietnam had asked the United States last year to revise its status from a “nonmarket economy” to a “market economy” to enjoy preferential tariff rates amidst deepening political and economic ties between the two countries. The change was opposed by the steel industry, shrimp fisheries, agriculture, and others who compete with imports from Vietnam, while there was also concern about Chinese exports evading U.S. tariffs through transshipment through Vietnam. Vietnam’s government has suggested it will reapply for market economy in the future.

Evading Controls: A report by the New York Times found that semiconductors and other equipment covered by export controls implemented by the Biden administration in October 2022 are still finding their way into China. A combination of smuggling, foreign subsidiaries, shell companies, weak oversight, and more have combined to continue imports of some of the restricted technologies into China, with one sale as large as $103 million.

China Sues EU: China has filed a lawsuit at the World Trade Organization (WTO) against the European Union for its recently announced tariffs against electric vehicle (EV) imports from China. China and the EU have been working on a negotiated settlement to the dispute, and the lawsuit represents an escalation of the dispute.

Analysis: Does the U.S. Election Even Matter for Economic Statecraft?

One of the most notable features of the Biden administration’s international economic strategy has been its continuity with the preceding Trump administration. The Biden administration kept the Trump administration’s tariffs on China in place and even expanded them in some instances, it continued the Trump administration’s hardline approach toward the World Trade Organization’s dispute settlement process, and its overall willingness to use economic coercion more aggressively and less apologetically than in the past. For all of the concern in Tokyo about “moshi Tora?” – what if Trump? – a concern shared throughout the region, the more important question might be, does it even matter?

The case for continuity is pretty solid. The fact that a basic model of economic statecraft has persisted across administrations of different parties points to the reality that these measures are now baked in to U.S. statecraft. Status quo bias and path dependency mean it’s difficult to imagine a scenario where decision makers would willingly step back from the economic security state that they’ve created. These tools are also relatively low cost compared to other tools (though not cost-free) and target states are much less capable of pushing back given the depth and extent of U.S. economic networks.

More specifically, political anxiety with China and the push for geopolitical competition in Washington aren’t going away anytime soon. Regardless of the administration, voices from Congress will likely continue to push for a hard line toward China regarding economics. The government bureaucracies responsible for administering economic statecraft are larger, better staffed, and have more extensive remits, buttressed by the fact that economic statecraft remains an appealing tool for decision makers who may not want to commit military force to accomplish strategic goals and it’s a far easier sell to the public.

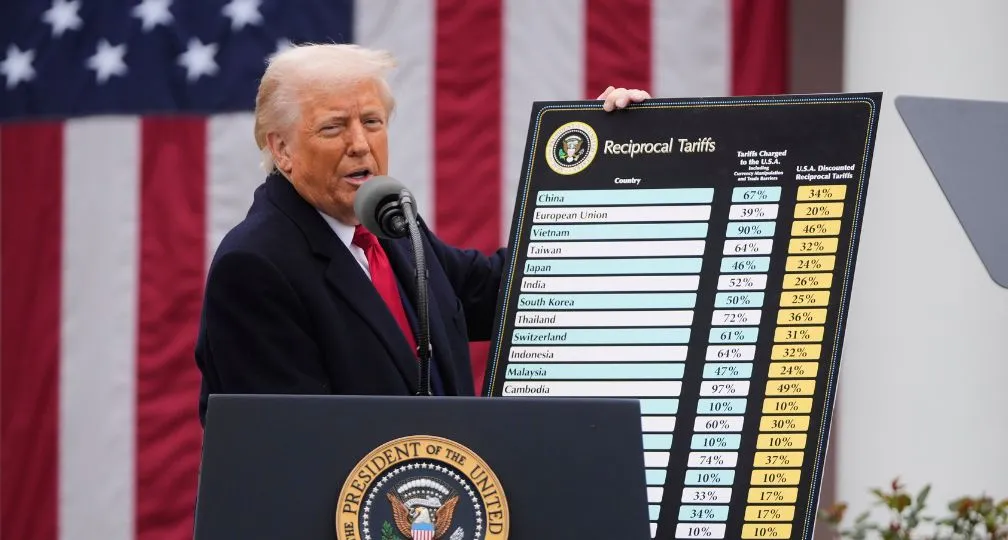

But the case for change is strong too. The first Trump administration was unusually focused on trade policy and he aims to be even more assertive on trade issues if he returns to the White House. The 2024 Republican Party platform calls for baseline tariffs on all foreign goods (Trump himself has suggested 10 percent, and as much as 60 percent on goods from China), and the passage of legislation enabling the president impose reciprocal tariffs on any country imposing tariffs on the United States. Other possible moves include revoking Most Favored Nation status from China, repatriating supply chains, strengthening Buy American policies, pulling back from electric vehicle mandates, and restoring manufacturing. Along with China, the European Union would also be a target for tariffs under a second Trump administration, along with possibly Brazil and India.

Of course, it’s worth remembering that Trump doesn’t see tariffs only as a measure of protectionism but also a way to build leverage to shape dealmaking in other spaces. But whatever the motivation, countries would respond to a Trump election by bracing for new tariffs and acting accordingly. There are also second- and third-order effects to consider, since Trump’s proposed tariffs, especially when joined with his proposed tax cuts and a looser monetary policy, would probably contribute to a spike in inflation (Trump dismisses these concerns along with the idea that businesses may pass the additional costs onto consumers) and weaken the value of the dollar, which would have their own set of impacts across the international economy.

There could also be change if Kamala Harris wins, and in this case the changes will be more subtle but may eventually be profound. Harris herself generally hasn’t prioritized trade policy to this point in her career. She’s described Trump’s tariffs as a “Trump trade tax” and has shown openness to some trade deals and skepticism towards others with an emphasis on issues like climate change and workers’ rights. The main substance of her approach to these issues will be shaped by her advisors and the general direction on the Democratic Party. It’s likely that a Harris administration will draw from many of the same people from the Biden administration, while accounting for the usual turnover that accompanies every term in office.

More generally, Democrats haven’t strayed much from their identity as a trade-skeptic party (Bill Clinton and Barrack Obama pursued trade liberalization like NAFTA and other agreements over the objections of party members rather than enjoying a unified coalition). Consistent with the direction of Democrats’ approach to trade agreements, Harris will probably continue to emphasize issues like worker protections and labor rights, environmental protections, and climate change. The question for partner countries is whether a hypothetical Harris administration would recommit to the multilateral order through the World Trade Organization, coordinating with allies and partners on tools of economic coercion, and the like. Foreign partners may be able to shape a Harris administration’s views on trade issues of particular importance to them, but recent Democratic administrations have been more insular regarding advice from outside, so while foreign governments could make their case, the results might be limited.

But as the Cato Institute’s Simon Lester points out, it’s worth asking what happens to Republican trade policy if Trump and his protectionist platform loses for a second straight election. The political landscape for trade policy in the United States hasn’t changed as dramatically as sometimes assumed except the fact that pro-trade, pro-market Republicans have almost completely evaporated as a political force. The 2024 Republican Party platform has shown the degree to which the Party has been captured by Trump’s economic platform, which has in turn made it harder for pro-trade Democrats to find Republican votes to make up for the opposition from their own party.

Yet Trump’s dominance can’t last forever and it’s not clear if the protectionism he’s advocated would last as a feature of the Republican Party. And if Republicans become less protectionist, there in turn may be less pressure for Democrats to be a protectionist party if they’re not worried about trying to out-protectionist Trump in what they see as competition for blue-collar votes in Rust Belt swing states. This doesn’t mean a return to 1990s-style globalism, but it might remove some of the pressure to take market liberalization entirely off the table or to come out against foreign acquisitions like Nippon Steel’s proposed acquisition of U.S. Steel.

So the question of “does it matter?” is “yes” and “no” – no, because certain features of economic statecraft are baked-in; yes, because the candidates have meaningful differences on these issues that will play out in possibly profound ways in the future. Which future is better is for everyone to decide for themselves, but either way, the outcome will be pivotal for the future of U.S. international economic strategy.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this IOG Economic Intelligence Report do not necessarily reflect those of the API, the Institute of Geoeconomics (IOG) or any other organizations to which the author belongs.

API/IOG English Newsletter

Edited by Paul Nadeau, the newsletter will monthly keep up to date on geoeconomic agenda, IOG Intelligencce report, geoeconomics briefings, IOG geoeconomic insights, new publications, events, research activities, media coverage, and more.

Visiting Research Fellow

Paul Nadeau is an adjunct assistant professor at Temple University's Japan campus, co-founder & editor of Tokyo Review, and an adjunct fellow with the Scholl Chair in International Business at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). He was previously a private secretary with the Japanese Diet and as a member of the foreign affairs and trade staff of Senator Olympia Snowe. He holds a B.A. from the George Washington University, an M.A. in law and diplomacy from the Fletcher School at Tufts University, and a PhD from the University of Tokyo's Graduate School of Public Policy. His research focuses on the intersection of domestic and international politics, with specific focuses on political partisanship and international trade policy. His commentary has appeared on BBC News, New York Times, Nikkei Asian Review, Japan Times, and more.

View Profile-

Will Trump’s tech policies propel U.S. success against China?2025.08.08

Will Trump’s tech policies propel U.S. success against China?2025.08.08 -

The “Reciprocal” Tariffs Are Now in Effect – But for How Long?2025.08.07

The “Reciprocal” Tariffs Are Now in Effect – But for How Long?2025.08.07 -

The rift between Trump and the EU: can Italy’s Meloni become a bridge-builder?2025.08.06

The rift between Trump and the EU: can Italy’s Meloni become a bridge-builder?2025.08.06 -

Tariff Tracker: A Guide to Tariff Authorities and their Uses2025.08.06

Tariff Tracker: A Guide to Tariff Authorities and their Uses2025.08.06 -

Japan’s Upper House Election: Political Fragmentation and Growing Instability2025.07.25

Japan’s Upper House Election: Political Fragmentation and Growing Instability2025.07.25

Japan’s Upper House Election: Political Fragmentation and Growing Instability2025.07.25

Japan’s Upper House Election: Political Fragmentation and Growing Instability2025.07.25 Why the EU economy faces hard choices between Trump and China2025.07.24

Why the EU economy faces hard choices between Trump and China2025.07.24 The “Reciprocal” Tariffs Are Now in Effect – But for How Long?2025.08.07

The “Reciprocal” Tariffs Are Now in Effect – But for How Long?2025.08.07 DOGE Shock and Crisis in U.S. Credibility2025.07.14

DOGE Shock and Crisis in U.S. Credibility2025.07.14 Unchecked and unbalanced: The future of U.S. economic policymaking2025.07.07

Unchecked and unbalanced: The future of U.S. economic policymaking2025.07.07